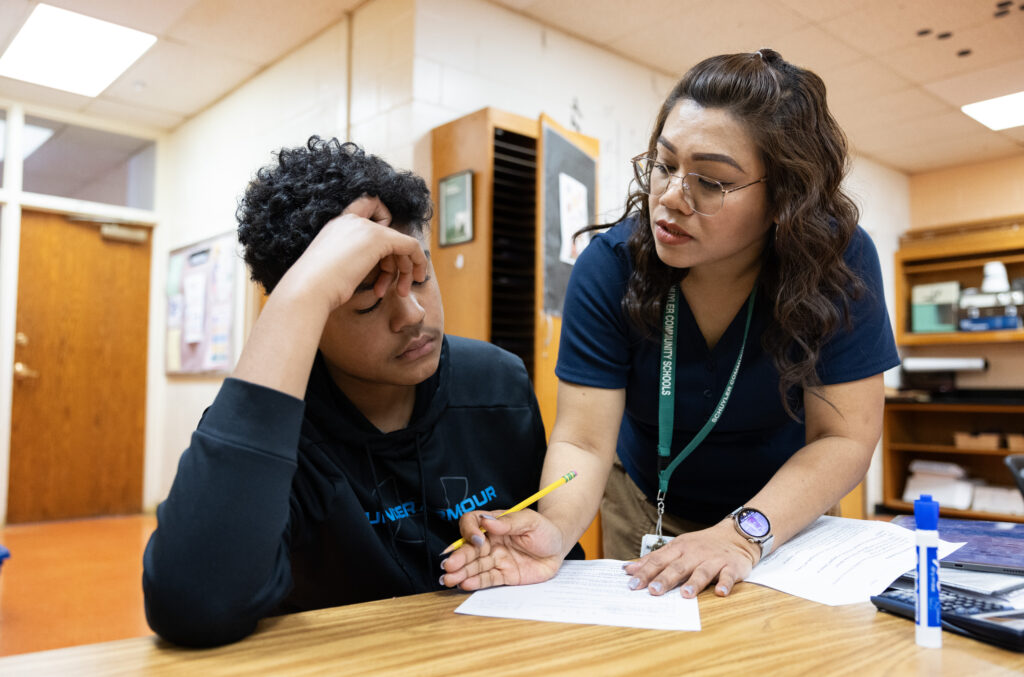

SCHUYLER — In a classroom 7,903 miles from home, Dorina Ramos counts down from five.

“Five,” Ramos says in her clear and practiced English, as a teenager passing around handfuls of chips sits back at his desk.

“Four.” A lingering high schooler stores his school-issued iPad away in a classroom cabinet.

“Three.” Another teenager wanders from the pencil sharpener back to her seat.

“Two.” The Spanish chatter of Ramos’ class of immigrant high schoolers falls to a hush.

“One.”

They pull the day’s worksheet on the mirror equation and magnification formulas out of their folders.

Counting down is a new strategy for Ramos, a classroom management tactic she picked up after arriving in Schuyler.

“They know that after that time, if they are still misbehaving, they will be reported to the office,” the 37-year-old teacher said.

Nine months ago, Ramos and 12 other teachers left their lives in the Philippines — homes, families, friends — to teach at Schuyler Community Schools, joining the growing number of Filipino teachers across the state who accept the jobs school districts are desperate to fill.

In Nebraska, vacant teacher jobs are still three times as high as they were the year before the COVID-19 pandemic. More teachers than ever are leaving the profession, administrators said, and not enough new teachers are entering it.

Colleges and the state have pursued long-term attempts to fix the teacher pipeline. But in the short term, schools have started to look internationally. At least eight Nebraska school districts — many of them rural — have hired from the Philippines. More still are considering it.

“We knew that (the) teacher shortage was coming, because candidates were becoming very thin. So we wanted to give it a shot. Which, thank God we did, because without those staff, all those positions would have been vacant,” said Kevin Mills, director of human resources for North Platte Public Schools, which hired six Filipino teachers two years ago.

But challenges arise when hiring internationally, said Tim Royers, president of the Nebraska State Education Association, the union representing teachers. And, he said, if fails to address the systemic problems facing the profession.

“If you’re turning to a solution because you can’t find anybody else — whether that’s an international teacher, whether that’s an alternative certification pathway — if you’re turning to that solution in desperation, you’re making the wrong move period,” Royers said.

***

Blocks away from the high school where Ramos teaches, Rona Cariit walks between the desks of her brood of second graders. She compliments their handwriting, makes sure their letters stay between the lines.

“Class class,” she says.

“Yes yes?” they reply.

“Are you ready for the next activity?”

A high-pitched chorus of yeses responds, ready to go over spelling words.

Principals at Schuyler Community Schools had been getting applicants from the Philippines for years, said Alicia Keairnes, assistant principal at the elementary school. But they’d pretty much ignored international applications.

Now, international applications are about all they see, she said.

Last school year, nearly 50 teachers left the district, a mix of early retirements and resignations. The turnover was double what the district saw the year before.

It was time to consider those international applications.

“We got to the point where we had to fill the classrooms, and there just were not enough teachers,” said Bill Comley, head principal at the elementary school.

No one tracks how many Nebraska districts have hired abroad. But the Flatwater Free Press found such districts in suburban Omaha, and northeast Nebraska cities like Columbus and Schuyler. Tiny Loup County in the Sandhills hired an English teacher. North Platte to the west brought in six new teachers. Walthill on the Omaha reservation hired a music teacher. In total, at least eight districts have hired teachers from the Philippines.

The two countries have similar curriculums and grading systems, and similar school calendars, making teachers from the Philippines a good fit for schools in the U.S.

In Schuyler, administrators turned to the recruiting company Praxical Strategies, which arranges interviews and handles immigration paperwork and background checks. Schuyler’s international teachers are hired on H-1B visas, which offer a path to a green card and let teachers bring their families to Nebraska. The teachers are paid the same salary as their American counterparts, and are represented by the teachers union.

“Our hope was not to bring them here on a business transaction,” Comley said. “Our job is to actually hope they want to stay and be a part of the community.”

***

School districts used to get dozens — sometimes hundreds — of applicants for teaching jobs, said Bret Schroder, the superintendent in Schuyler. Now, it’s common to get one or two applicants. Sometimes, they get none at all.

In 2023, unfilled teaching jobs in the state peaked at 908, according to the Nebraska Department of Education’s annual vacancy survey. An unfilled position includes both positions left vacant and positions filled by someone other than a fully qualified teacher. Of those 908 unfilled jobs, 361 were left empty.

That number has gone down a bit. This past school year, Nebraska had 669 unfilled positions and 200 vacant positions. But that’s still higher than the years before the COVID-19 pandemic. While the annual vacancy survey shows improvement, the numbers can be misleading. If a district gives up on hiring and cuts a position entirely, that’s no longer counted as an unfilled job, Royers said.

Fewer people are entering the profession. In 2012, 1,804 people completed teacher prep programs at Nebraska colleges. That dropped to 1,366 people in 2022.

Schools and colleges have tried to reverse that trend, said Paul Turman, chancellor of the Nebraska State College System. More high schools are offering dual credit programs, where students can start earning credits for their teaching degree in high school. A scholarship program helps students pay for their teaching degree, so long as they stay to teach in Nebraska after graduating. It’s becoming easier for paraprofessionals to get their teaching certification.

Still, the number of graduates entering the profession “most certainly needs to be higher,” Turman said.

More teachers are also leaving the job early, as Schuyler saw last year.

Nebraska had 461 fewer full-time teachers in 2023 compared to 2012, according to state Department of Education data.

When Royers started doing union work in 2010, 80% of turnover was because of retirement. The other 20% were leaving to work in other districts, or simply leaving the profession. Now, that’s almost inverted, he said.

Teachers are citing extreme burnout and are struggling with student behavior, according to teachers’ union surveys.

“It’s almost like this death spiral,” Royers said of the turnover. “You have this burnout; people are leaving the profession. They can’t fill the positions. That leads to higher class sizes and higher case loads. More folks get burnt out, more folks walk away.”

And, he said, hiring internationally isn’t helping.

“To hire folks from another country to do those roles that they can’t fill because they’re not electing to adopt policies that their teachers are asking for, makes (teachers) feel even more unwanted,” Royers said. There’s “resentment that they’re willing to go to this extreme, rather than addressing the solutions we’ve been advocating for.”

Schroder said he would love to hire teachers from Nebraska and surrounding states. But the shortage of applicants has forced districts to find solutions now.

“I want to see more young people go into teaching. And having teachers stay in the profession longer would be a positive step … but that doesn’t address the need right now of not having enough teachers to fill classrooms across not only our state, but our country,” he said.

***

Ramos stepped off the plane in Omaha with two other teachers she’d never met before.

It was around midnight as they made their way through Eppley Airfield looking for her soon-to-be boss.

Dave Cunningham wore no Schuyler gear. He didn’t have a sign. He hadn’t interviewed the teachers — it was his first year as high school principal, so his predecessor had been the one to talk to the new hires over video call. But he’d seen their pictures.

“Schuyler?” the tall, looming principal said as the trio of teachers approached him.

“These are the teachers?” his son asked. “Why are they so small?”

The drive back to Schuyler was filled with questions. What was the town like? What was there to do? How far from Omaha was it?

Ramos had been traveling for 24 hours, on three flights. She’d left behind her husband and two daughters. With 16 years of teaching experience, she’d interviewed with schools in North Carolina, Texas, and Alaska before accepting the job in Schuyler. She’d even taken out a loan to cover the nearly $10,000 that went to the recruiting company, her plane ticket,t and passport processing fees.

But it was OK, she said. In the Philippines, saying you’ve worked in the U.S. is a big deal. She wanted to learn more about teaching and technology and western culture. And she could make more money in Nebraska than she ever could in the Philippines.

Teaching was a childhood dream for Ramos, inspired by the teachers she had growing up. As a kid, she helped her younger siblings with their schoolwork. In college, she majored in physics, then got her master’s in teaching.

She traveled to Schuyler from Batangas, a city of about 350,000 people, where farming corn and tomatoes and raising pigs and cows drives the economy.

Before Ramos and the other teachers even got to Nebraska, elementary school principals Comley and Keairnes were lining up rental houses and furniture for them.

They learned to be wary of scammers — when the district released the names of new hires in school board minutes, the teachers in the Philippines started getting ads for Schuyler homes that didn’t exist, asking them to send a deposit to secure a place to live.

Once the teachers arrived, the pair of principals helped them set up bank accounts and cell phones, and get Social Security numbers. They found someone local who could teach them to drive. For months, Comley and Keairnes gave teachers rides to school.

“We have to get them on their feet so that they feel like they are supported and confident that their living situation, their basic needs are met first,” Keairnes said. “Because we can’t expect them to take care of 20 kids in a classroom when their own basic needs aren’t met.”

Teaching in America comes with a mental toll. There’s a 13-hour time difference between Nebraska and the Philippines. Ramos talks to her family at 6 p.m., Schuyler time, when it’s 7 a.m. at home. Many teachers had to cancel plans to visit home after President Donald Trump took office and started making sweeping immigration changes. They were scared that they’d have visa issues when returning to the States.

There are similarities between the two education systems that make it easier for Filipino teachers to get certified here. But there are key classroom differences, too. In the Philippines, yelling at students is acceptable, Cariit said. Students in the Philippines give their teachers gifts every holiday, and all say good morning when they enter the classroom each day. Ramos’s high schoolers roll in sleepy and quiet.

Schools in the Philippines use textbooks, rather than iPads and smartboards. The government strictly determines lesson plans and what goes on the walls. And teachers pay for all of their materials, even down to cleaning supplies. During staff meals, teachers serve the principals. Here, Ramos was shocked to see Cunningham serving lunch to teachers.

The work of helping international teachers acclimate to teaching in the U.S. often falls to other teachers in the building, Royers said, adding more responsibilities to their already stacked plate.

“I feel incredibly bad for these international teachers coming in, because they’re almost set up to fail,” Royers said. “There’s no scenario where they can succeed or thrive, either on a personal level or on a professional level.”

But administrators in Schuyler said that was a concern on their minds before they even hired their first teacher from the Philippines.

In the past year, administrators have watched their teachers grow more confident in managing student behavior, as well as in their English and pronunciation, Comley said. The first couple of months were difficult, Ramos said, and some classes are harder to manage than others. But she feels more capable in her classroom, and ready for a second school year.

The Schuyler teachers have connected with other Filipino teachers working in Columbus, and Filipino phlebotomists working at CHI Health’s Schuyler clinic. They gather to celebrate Filipino holidays, cook traditional meals together, and sing karaoke, Ramos said. An elementary school custodian from the Philippines connected with the teachers on social media before they even arrived in Schuyler, Comley said.

All 13 of the teachers from the Philippines plan to return to Schuyler for a second school year. Six more will join them.

“These are folks who are well-trained educators with master’s degrees and doctorates and years of experience,” Schroder said. “They may be bringing skills and strengths and approaches to teaching that we haven’t looked at yet. So what can we learn from them?”